In the sweltering late-morning heat, Benjamin Musoro sits on a wooden stool on his veranda in Kuwadzana, a high-density suburb west of Zimbabwe’s capital Harare.

Squinting at the screen on his entry-level mobile, the 71-year-old father of five tops up his account with the Zimbabwe Power Company (ZPC)- the state electricity provider.

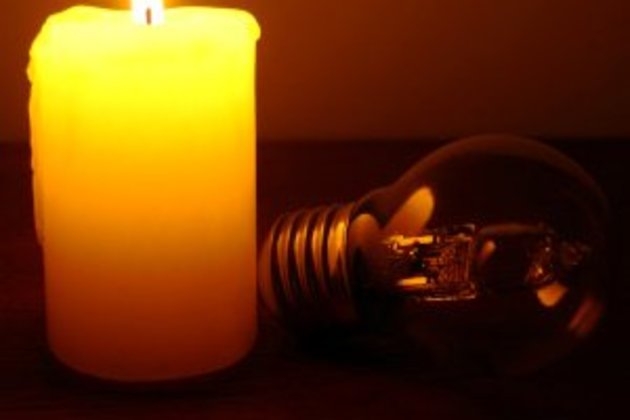

When his lights and television set went dark the previous evening, it was a sure sign his balance was negative.

“The cost of electricity is too high,” he told Al Jazeera.

For most of last year, Musoro’s biggest problem stemmed from a lack of available power. Hit by a combination of man-made and natural challenges, the state power company simply could not generate enough electricity to keep up with demand, forcing it to institute blackouts for up to 17 hours a day.

Since last fall, though, routine outages have been minimised to a few hours and only on isolated days, but not because more power is available.

Electricity tariffs in Zimbabwe skyrocketed in October 2019, when the Zimbabwe Energy Regulatory Authority (ZERA) approved an application by ZPC’s parent company – the Zimbabwe Electricity Transmission and Distribution Company (ZETDC) – to dramatically increase tariffs.

The price hike aimed to curtail household power consumption, bring tariffs in line with inflation, and eliminate subsidies the Zimbabwean government can ill afford.

But wages have not kept pace with the country’s blistering inflation. And the squeeze on household finances has now become a stranglehold after the regulator approved another 50 percent tariff increase late last month.Forcing tough choices

Last year’s rate increase had already forced consumers to make tough choices about how to allocate their precious power usage.

Musoro, who shares his homestead – an eight-room main house and a separate cottage – with four other families, has restricted power use to lights, televisions and refrigerators only.

Cooking, which can lead to a punitive bill totalling thousands of Zimbabwean dollars, did not make the cut.

“We no longer use electricity for cooking here,” he said. “We are struggling to pay 700 [Zimbabwean] dollars for electricity as it is. It’s going to be harder with the [tariff] increase.”

At the official exchange rate, 700 Zimbabwean dollars buys $8.5 (USD).

Zimbabwe is in the throes of a prolonged and festering economic crisis. Inflation running more than 800 percent and foreign currency shortages that have led to stomach-churning currency devaluations have been exacerbated by stagnant salaries that cannot keep pace with soaring prices.

The coronavirus pandemic has only heaped more hardships onto the nation’s financially embattled population.

Teachers in Zimbabwe earn approximately $50 every month. Pensioners receive less than $10 a month.

Even private-sector workers in their prime fret about how they will cope with yet another tariff rise.

Kingston Simbulani, a 46-year-old metal worker, splits the power bill with another tenant in his home. Together, they spend 400 Zimbabwean dollars ($4.83) every month on energy.

“I really can’t afford the new electricity tariffs,” Simbulani told Al Jazeera.